Annie Duke

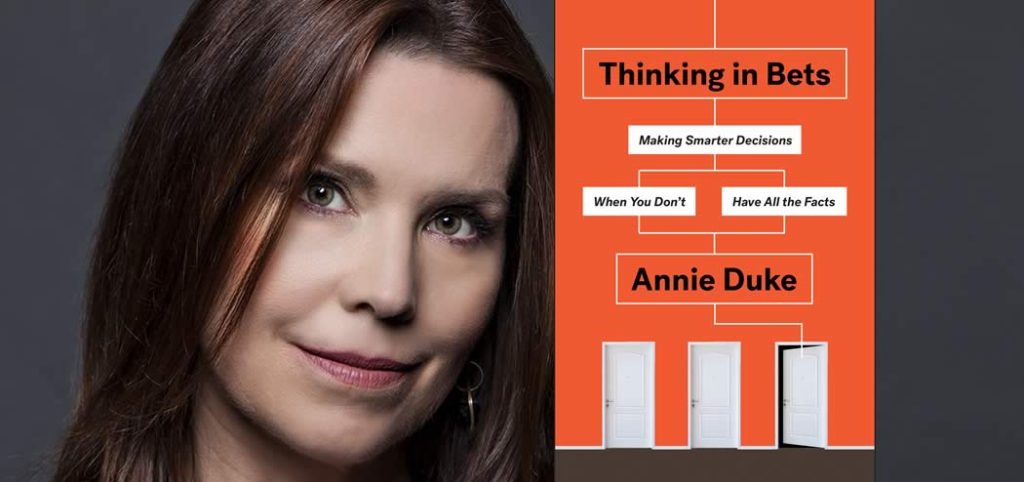

Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter

Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts

INTRODUCTION: Why This Isn’t aPoker Book

A hand of poker takes about two minutes.

Over the course of that hand, I could be involved in up to twenty decisions.

And each hand ends with a concrete result: I win money or I lose money. they handled not only luck and uncertainty but also the relationship between learning and decision-making.

bet really is: a decision about an uncertain future. The implications of treating decisions as bets made it possible for me to find learning opportunities in uncertain environments.

Treating decisions as bets, I discovered, helped me avoid common decision traps, learn from results in a more rational way, and keep emotions out of the process as much as possible.

The promise of this book is that thinking in bets will improve decision-making throughout our lives.

learn strategies to map out the future, become less reactive decision-makers, build and sustain pods of fellow

truthseekers to improve our decision process, and recruit our past and future selves to make fewer emotional decisions.

Thinking in bets starts with

recognizing that there are exactly two things that determine how our lives turn out: the quality of our decisions and luck. Learning to recognize the difference between the two is what thinking in bets is all about.

CHAPTER 1: Life Is Poker, Not Chess

One of the most controversial decisions in Super Bowl history took place in the closing seconds of Super Bowl XLIX in 2015.

He made a good-quality decision

that got a bad result.

Pete Carroll was a victim of our tendency to equate the quality of a decision with the quality of its outcome.

Poker players have a word for this: “resulting.” When I started playing poker,

more experienced players warned me about the dangers of resulting, cautioning

me to resist the temptation to change my strategy just because a few hands

didn’t turn out well in the short run.

Take a moment to imagine your best decision in the last year.

resulting is a routine thinking

pattern that bedevils all of us.

Hindsight bias is the tendency,

after an outcome is known, to see the outcome as having been inevitable.

Those beliefs develop from an overly tight connection between outcomes and decisions.

He decided he drove better when he was drunk.

Quick or dead: our brains weren’t built for rationality

behavioral economics.

To start, our brains evolved to create certainty and order.

Michael Shermer, in The Believing

Brain, explains why we have historically (and prehistorically) looked for

connections even if they were doubtful or false.

Seeking certainty helped keep us

alive all this time, but it can wreak havoc on our decisions in an uncertain world.

Daniel Kahneman, in his 2011

best-selling Thinking, Fast and Slow, popularized the labels of “System 1” and

“System 2.”

System 1

your car. It encompasses reflex,

instinct, intuition, impulse, and automatic processing.

System 2, “slow thinking,” is how

we choose, concentrate, and expend mental energy.

I particularly like the descriptive labels “reflexive mind” and “deliberative mind” favored by psychologist Gary Marcus. In his 2008 book, Kluge: The Haphazard Evolution of the Human Mind, he

wrote, “Our thinking can be divided into two streams, one that is fast, automatic, and largely unconscious, and another that is slow, deliberate, and judicious.”

Colin Camerer, a professor of behavioral economics at Caltech and leading speaker and researcher on the

intersection of game theory and neuroscience,

Making more rational decisions isn’t just a matter of willpower or consciously handling more decisions in

deliberative mind.

It turns out that poker is a greatplace to find practical strategies to get the execution of our decisions to

align better with our goals.

Our goal is to get our reflexive minds to execute on our deliberative minds’ best intentions.

players get in about thirty hands per hour.

of seventy seconds

Every hand (and therefore every decision) has immediate financial consequences.

All the talent in the world won’t matter if a player can’t execute;

John von Neumann

Theory of Games and Economic Behavior in 1944.

The Boston Public Library’s list of the “100 Most Influential Books of the Century” includes Theory of Games. William Poundstone, author of a widely read book on game theory, Prisoner’s

Dilemma, called it “one of the most influential and least-read books of the

twentieth century.”

A Beautiful Mind. “the study of mathematical models of conflict and cooperation between intelligent rational decision-makers.”

Poker vs. chess

‘Chess is not a game. Chess is a well-defined form of computation.

Real life consists of bluffing, of little tactics of deception, of asking yourself what is the other man going to think I mean to do. And that is what games are about in my theory.’”

Trouble follows when we treat life decisions as if they were chess decisions.

Chess contains no hidden information and very little luck.

where most of our decisions involve hidden information and a much greater influence of luck.

Poker, in contrast, is a game of incomplete information. It is a game of decision-making under conditions of

uncertainty over time. (Not coincidentally, that is close to the definition of

game theory.) Valuable information remains hidden. There is also an element of luck

in any outcome. You could make the best possible decision at every point and

still lose the hand, because you don’t know what new cards will be dealt and

revealed. Once the game is finished and you try to learn from the results, separating

the quality of your decisions from the influence of luck is difficult.

If we want to improve in any game—as well as in any aspect of our lives—we have to learn from the results of our decisions.

‘Never get involved in a land war in Asia,’

‘Never go in against a Sicilian when death is on the line.’”

But, also like all of us, he underestimated the amount and effect of what he didn’t know.

“I’m not sure.”

“I’m not sure”: using uncertainty to our

advantage

William Goldman

“I don’t want to be the man who learns. I want to be the man who knows.”

We have to make peace with not knowing.

acquiring knowledge, but the first step is understanding what we don’t know.

“Thoroughly conscious ignorance is the prelude to every real advance in science.”

What makes a decision great is not

that it has a great outcome. A great decision is the result of a good process,

and that process must include an attempt to accurately represent our own state

of knowledge. That state of knowledge, in turn, is some variation of “I’m not sure.”

The veteran will just have a better guess.

“I’m not sure”

If we misrepresent the world at the

extremes of right and wrong, with no shades of grey in between, our ability to

make good choices—choices about how we are supposed to be allocating our resources,

what kind of decisions we are supposed to be making, and what kind of actions

we are supposed to be taking—will suffer.

Redefining wrong

It just means that one event in a

set of possible futures occurred.

Any prediction that is not 0% or

100% can’t be wrong solely because the most likely future doesn’t unfold.

The second-best choice isn’t wrong.

By definition, it is more right (or less wrong) than the third-best or

fourth-best choice.

When we move away from a world

where there are only two opposing and discrete boxes that decisions can be put

in—right or wrong—we start living in the continuum between the extremes. Making

better decisions stops being about wrong or right but about calibrating among all

the shades of grey.

allocation of resources (a bet)

Don’t fall in love or even date

anybody if you want only positive results.

Second, being wrong hurts us more

than being right feels good.

We know from Daniel Kahneman and

Amos Tversky’s work on loss aversion, part of prospect theory (which won

Kahneman the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002), that losses in general feel

about two times as bad as wins feel good.

that means we need two favorable results for every one unfavorable result just to break even emotionally.

CHAPTER 2: Wanna bet?

“Johnny World,”

You have to put your money whereyour mouth is.

All decisions are bets

“bet” as “a choice made by thinking about what will probably happen,”

fold, check, call, bet, or raise.

Most bets are bets against ourselves

In most of our decisions, we are not betting against another person. Rather, we are betting against all the future versions of ourselves that we are not choosing.

We are betting that the future version of us that results from the decisions we make will be better off. At stake in a decision is that the return to us (measured in money, time,

happiness, health, or whatever we value in that circumstance) will be greater than what we are giving up by betting against the other alternative future versions of us.

Things outside our control (luck)

can influence the result.

The futures we imagine are merely possible.

Poker players live in a world where that risk is made explicit.

They can get comfortable with uncertainty because they put it up front in their decisions.

Our bets are only as good as our beliefs

We bet based on what we believe about the world.

Our beliefs drive the bets we make:

part of the skill in life comes from learning to be a better belief calibrator, using experience and information to more objectively update our beliefs to more accurately represent the world.

Hearing is believing

“Who here knows how you can predict if a man will go bald?”

“Does anyone know how you calculate a dog’s age in human years?”

“common misconceptions,”

As Medical Daily explained in 2015,

“a key gene for baldness is on the X chromosome, which you get from your mother”

We form beliefs in a haphazard way, believing all sorts of things based just on what we hear out in the world but haven’t researched for ourselves.

This is how we think we form abstract beliefs: We hear something; We think about it and vet it, determining whether it is true or false; only after that We form our belief.

It turns out, though, that we actually form abstract beliefs this way: We hear something; We believe it to be true; Only sometimes, later, if we have the time or the inclination, we think

about it and vet it, determining whether it is, in fact, true or false.

“Findings from a multitude of research

literatures converge on a single point: People are credulous creatures who find

it very easy to believe and very difficult to doubt. In fact, believing is so easy, and perhaps so inevitable, that it may be more like involuntary comprehension than it is like rational assessment.”

This suggests our default setting is to believe what we hear is true.

how we form beliefs was shaped by the evolutionary push toward efficiency rather than accuracy.

Before language, our ancestors

could form new beliefs only through what they directly experienced of the physical world around them.

type I errors (false positives)

were less costly than type II errors (false negatives). In other words, better

to be safe than sorry, especially when considering whether to believe that the

rustling in the grass is a lion.

(1) experience it, (2) believe it to be true,

and (3) maybe, and rarely, question it later.

Texas Hold’em

In poker shorthand, such cards are

called “suited connectors.”

“win big or lose small with suited connectors”

Truthseeking, the desire to know

the truth regardless of whether the truth aligns with the beliefs we currently

hold, is not naturally supported by the way we process information. We might

think of ourselves as open-minded and capable of updating our beliefs based on

new information, but the research conclusively shows otherwise. Instead of

altering our beliefs to fit new information, we do the opposite, altering our

interpretation of that information to fit our beliefs.

The stubbornness of beliefs

information-processing pattern is called motivated reasoning.

news in that the story has some

true elements, embellished to spin a particular narrative. Fake news works because people who already hold beliefs consistent with the story generally won’t question the evidence.

Every flavor is out there, but we tend to stick with our favorite.

like. Author Eli Pariser developed the term “filter bubble” in his 2011

The most popular websites have been doing our motivated reasoning for us.*

Part of being “smart” is being good at processing information, parsing the quality of an argument and the credibility of the source.

being smart can actually make bias worse.

the smarter you are, the better you are at constructing a narrative that supports your beliefs, rationalizing and framing the data to fit your argument or point of view.

we all have a blind spot about recognizing

our biases.

The surprise is that blind-spot bias is greater the smarter you are.

We are wired to protect our beliefs even when our goal is to truthseek.

Just as we can’t unsee an illusion,

intellect or willpower alone can’t make us resist motivated reasoning.

And the person who wins bets over

the long run is the one with the more accurate beliefs.

“Wanna bet?”

We are less likely to succumb to

motivated reasoning since it feels better to make small adjustments in degrees

of certainty instead of having to grossly downgrade from “right” to “wrong.”

There is no sin in finding out

there is evidence that contradicts what we believe.

The fact that the person is

expressing their confidence as less than 100% signals that they are trying to

get at the truth, that they have considered the quantity and quality of their

information with thoughtfulness and self-awareness.

Expressing our level of confidence

also invites people to be our collaborators.

First, they might be afraid they

are wrong and so won’t speak up, worried they will be judged for that, by us or

themselves. Second, even if they are very confident their information is high

quality, they might be afraid of making us feel bad or judged.

Acknowledging that decisions are bets

based on our beliefs, getting comfortable with uncertainty, and redefining

right and wrong are integral to a good overall approach to decision-making.

CHAPTER 3: Bet to Learn: Fielding

the Unfolding Future

He fixated on the relatively common

belief that the element of surprise was important in poker.

I was taught, as all psychology students are, that learning occurs when you get lots of feedback tied closely in time to decisions and actions.

The answer is that while experience is necessary to becoming an expert, it’s not sufficient.

Outcomes are feedback

We can’t just “absorb” experiences and expect to learn.

Aldous Huxley recognized,

“Experience is not what happens to a man; it is what a man does with what

happens to him.”

Ideally, our beliefs and our bets improve with time as we learn from experience.

When the future coughs on us, it is

hard to tell why.

Rory McIlroy.

Outcomes don’t tell us what’s our

fault and what isn’t, what we should take credit for and what we shouldn’t.

His fielding error meant he never questioned his beliefs, no matter how much he lost.

Classical stimulus-response experiments have shown that the introduction of uncertainty drastically slows learning.

Slot machines operate on a variable-payoff system.

“If it weren’t for luck, I’d win every one”

“Self-serving bias” is the term for this pattern of fielding outcomes.

Phil Hellmuth, the biggest winner in World Series

“If it weren’t for luck, I’d win every one.”

Self-serving bias has immediate and

obvious consequences for our ability to learn from experience.*

Self-serving bias is a deeply embedded and robust thinking pattern.

All-or-nothing thinking rears its head again

Yogi Berra said, “You can observe a lot by watching.”

Watching is an established learning method.

That means about 80% of the time is spent just watching other people play.

That’s an opportunity to learn at no extra cost.

There’s a lot of free information out there.

As artist and writer Jean Cocteau said, “We must believe in luck. For how else can we explain the success of those we don’t like?”

Other people’s outcomes reflect on us

Taking credit for a win lifts our personal l narrative.

That’s schadenfreude: deriving pleasure from someone else’s misfortune. Schadenfreude is basically the opposite of compassion.

Wins and losses are symmetrical.

Our genes are competitive.

It’s not enough to boost our self-image solely by our own successes.

If someone we view as a peer is winning, we feel like we’re losing by comparison.

a supportive marriage, What accounts for most of the variance in happiness is how we’re doing comparatively.

A lot of the way we feel about ourselves comes from how we think we compare with others.

This robust and pervasive habit of mind impedes learning.

Reshaping habit

Habits operate in a neurological loop

the cue, the routine, and the reward.

the cue might be winning a hand, the routine taking credit for it, the reward a boost to our ego.

“To change a habit, you must keep the old cue, and deliver the old reward, but insert a new routine.”

Duhigg recognizes that respecting the habit loop means respecting the way our brain is built.

Our brain is built to seek positive self-image updates.

unproductive habits of mind of self-serving bias and motivated reasoning into productive ones.

Mia Hamm

Just as Duhigg recommends respecting

the habit loop, we can also respect that we are built for competition, and that our self-narrative doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

when I was eager to share a hand that I thought I played poorly because I might learn something from it, Ideally, we wouldn’t compare ourselves with others or get a good feeling when the comparison favors us.

“Wanna bet?” redux

It’s easy to win a bet against someone who takes extreme positions.)

We are more likely to explore the opposite side of an argument more often and more seriously—

Thinking in bets also triggers perspective taking,

Recruiting help is key to creating faster and more robust change,

CHAPTER 4 The Buddy System

“You take the blue pill, the story ends. You

wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red

pill, you stay in Wonderland and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.”

His job and lifestyle, his clothes,

his appearance, and the entire fabric of his life are an illusion implanted in his brain.

Nebuchadnezzar.

but one of the most obvious is that

other people can spot our errors better than we can. it is worth it to get a buddy to

watch your back—or your blind spot.

In fact, as long as there are three

people in the group (two to disagree and one to referee*), the truthseeking

group can be stable and productive.

To maintain sobriety, however, he

realized that he needed to talk to another alcoholic.

But, while a group can function to

be better than the sum of the individuals, it doesn’t automatically turn out that way..

but a group can also exacerbate our

tendency to confirm what we already believe.

Confirmatory thought promotes a love and celebration of one’s own beliefs, distorting how the group processes information and works through decisions, the result of which can be groupthink.

Exploratory thought, on the other

hand, encourages an open-minded and objective consideration of alternative

hypotheses and a tolerance of dissent to combat bias.

Without an explicit charter for

exploratory thought and accountability to that charter, our tendency when we interact with others follows our individual tendency, which is toward confirmation.

“echo chamber”

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People

Are Divided by Politics and Religion,

This is why it’s so important to

have intellectual and ideological diversity within any group or institution whose goal is to find truth.”

We don’t win bets by being in love with our own ideas.

In the long run, the more objective person will win against the more biased person.

betting is a form of accountability to accuracy.

The group rewards focus on accuracy

We all want to be thought well of, especially by people we respect.

our craving for approval is incredibly strong and incentivizing.

Exploratory thought becomes a new

habit of mind, the new routine, and one that is self-

Accountability is a willingness or obligation to answer for our actions or beliefs to others.

winning a bet triggers a reinforcing positive update.

“loss limit”—if I lost $ 600 at the stakes I

was playing, I would leave the game.

John Stuart Mill is one of the heroes of thinking in bets.

On Liberty,

A poker table is a naturally

diverse setting because we generally don’t select who we play with for their

opinions.

we can’t know the truth of a matter

without hearing the other side.

Diversity is the foundation of productive group decision-

We all tend to gravitate toward

people who are near clones of us.

“Our data provide strong evidence that

like-minded judges also go to extremes:

The more homogeneous we get, the

more the group will promote and amplify confirmatory thought.

Conservatives complain that

liberals live in an echo chamber where they just repeat and confirm their point

of view.

Heterodox Academy, to fight this

drift toward homogeneity of thought in science and academics as a whole.

In 2015, they published their

findings in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences (BBS),

Wanna bet (on science)?

CHAPTER 5: Dissent to Win

“role model,”

“self-fulfilling prophecy,” “reference group,”

“unintended consequences,” and “focus group.”

“more is more.”

As a rule of thumb, if we have an

urge to leave out a detail because it makes us uncomfortable or requires even

more clarification to explain away, those are exactly the details we must

share.

Rashomon Effect, named for the 1950

cinematic classic Rashomon,

Be a data sharer. That’s what

experts do.

In fact, that’s one of the reasons

experts become experts. They understand that sharing data is the best way to

move toward accuracy because it extracts insight from your listeners of the

highest fidelity.

the positions of everyone acting in

the hand; the size of the bets and the size of the pot after each action; what

they know about how their opponent( s) has played when they have encountered

them in the past; how they were playing in the particular game they were in;

how they were playing in the most recent hands in that game (particularly

whether they were winning or losing recently); how many chips each person had

throughout the hand; what their opponents know about them, etc., etc.

expert players essentially work from a template,

Universalism: don’t shoot the

message

Plutarch’s Life of Lucullus

provided an early, literal example: the king of Armenia

The Mertonian norm of universalism

is the converse.

don’t disparage or ignore an idea

just because you don’t like who or where it came from.

I had started thinking more deeply

about the way my opponents thought.

we forget the obvious truth that no

one has only good ideas or only bad ideas.

Another way to disentangle the

message from the messenger is to imagine the message coming from a source we

value much more or much less.

John Stuart Mill made it clear that

the only way to gain knowledge and approach truth is by examining every variety

of opinion.

Disinterestedness: we all have a

conflict of interest, and it’s contagious

Telling someone how a story ends

encourages them to be resulters, to interpret the details to fit that outcome.

The best way to do this is to

deconstruct decisions before an outcome is known.

After the outcome, make it a habit

when seeking advice to give the details without revealing the outcome.

Beliefs are also contagious.

Organized skepticism: real skeptics

make arguments and friends

Skepticism is about approaching the

world by asking why things might not be true rather than why they are true.

Without embracing uncertainty, we

can’t rationally bet on our beliefs.

“lean over backwards”

Expression of disagreement is,

after all, just another way to express our own beliefs, which we acknowledge

are probabilistic in nature.

Communicating with the world beyond

our group

First, express uncertainty.

Second, lead with assent.

“and” instead of “but.”

When we lead with assent, our

listeners will be more open to any dissent that might follow.

“And” is an offer to contribute. “But” is a

denial and repudiation of what came before.

a scene, you should respond with

“yes, and . . .” “Yes”

“And” means you are adding to it.

Third, ask for a temporary

agreement to engage in truthseeking.

By recruiting past and future

versions of yourself, you can become your own buddy.

CHAPTER 6: Adventures in Mental Time

Travel

“Whatever you do, don’t meet up with

yourself!”

“Don’t meet up with yourself”

As decision-makers, we want to

collide with past and future versions of ourselves.

we can recruit other versions of

ourselves to act as our own decision buddies.

Improving decision quality is about

increasing our chances of good outcomes, not guaranteeing them.

When we make in-the-moment

decisions (and don’t ponder the past or future), we are more likely to be irrational

and impulsive.*

This tendency we all have to favor

our present-self at the expense of our future-self is called temporal

discounting.*

We are willing to take an irrationally large discount to get a reward now instead of waiting for a bigger reward later.

Our vision of the future, rather, is rooted in our memories of the past.

The future we imagine is a novel reassembling of our past experiences.

Thinking about the future is remembering the future,

“Face Retirement.”

Philosophers agree that regret is

one of the most intense emotions we feel,

Nietzsche said that remorse was

“adding to the first act of stupidity a second.”

Suzy Welch developed a popular tool

known as 10-10-10 that has the effect of bringing future-us into more of our

in-the-moment decisions.

[W] hat are the consequences of each of my

options in ten minutes? In ten months? In ten years?”

“How would I feel today if I had made this

decision ten minutes ago? Ten months ago? Ten years ago?”

Recruiting past-us and future-us in

this way activates the neural pathways that engage the prefrontal cortex,

inhibiting emotional mind and keeping events in more rational perspective.

Our problem is that we’re ticker watchers of our own lives.

Happiness (however we individually define

it) is not best measured by looking at the ticker, zooming in and magnifying

moment-by-moment or day-by-day movements.

The zoom lens doesn’t just magnify,

it distorts.

Our feelings are not a reaction to

the average of how things are going.

like a stock ticker, reflects the

most recent changes, creating a risk that players get

Tilt is the poker player’s worst

enemy,

If you blow some recent event out

of proportion and react in a drastic way, you’re on tilt.

There are emotional and physiological signs of tilt.

Any kind of outcome has the potential

for causing an emotional reaction.

“why don’t you sleep on it?”

“It’s all just one long poker game.”

Ulysses contract.

(Most translations of Homer use the hero’s

ancient Greek name, Odysseus. The time-travel strategy uses the hero’s ancient

Roman name, Ulysses.)

When you are physically prohibited

from deciding, you are interrupted in the sense that you are prevented from acting

on an irrational impulse; the option simply isn’t there.

Decision swear jar

several patterns of irrationality

Signs of the illusion of certainty:

Overconfidence:

Irrational outcome fielding:

Any kind of moaning or complaining

about bad luck just to off-load it,

Generalized characterizations of

people meant to dismiss their ideas: insulting,

shooting the message because we

don’t think much of the messenger.

“gun nut,” “bleeding heart,” “East Coast,”

“Bible belter,” “California values”—political or social issues.

Also be on guard for the reverse:

accepting a message because of the messenger or praising a source immediately

after finding out it confirms your thinking.

Signals that we have zoomed in on a

moment,

“conventional wisdom” or “if you ask anybody”

or “Can you prove that it’s not true?” Similarly, look for expressions that

you’re participating in an echo chamber, like “everyone agrees with me.”

The word “wrong,” which deserves

its own swear jar.

Lack of self-

Infecting our listeners with a conflict

of interest, including our own conclusion or belief when asking for advice or

informing the listener of the outcome before getting their input.

Reconnaissance: mapping the future

Operation Overlord, the Allied

forces operation to retake German-occupied France starting in Normandy, was the

largest seaborne invasion in military history.

For us to make better decisions, we

need to perform reconnaissance on the future.

scenario planning.

“When faced with highly uncertain conditions,

military units and major corporations sometimes use an exercise called scenario

planning.

The reason why we do reconnaissance

is because we are uncertain.

It’s about acknowledging that we’re

already making a prediction about the future every time we make a decision, so

we’re better off if we make that explicit.

we’re worried about guessing, we’re

already guessing.

responses (fold, call, raise)

Being able to respond to the

changing future is a good thing; being surprised by the changing future is not.

we have memorialized all the

possible futures that could have happened.

Scenario planning in practice

The important thing is that we do

better when we scout all these futures and make decisions based on the

probabilities and desirability of the different futures.

Backcasting: working backward from

a positive future

“A journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step”?

When it comes to advance thinking,

standing at the end and looking backward is much more effective than looking

forward from the beginning.

The distorted view we get when we

look into the future from the present is similar to the stereotypical view of

the world by Manhattan residents,

When we forecast the future, we run

the risk of a similar distortion.

Imagining the future recruits the

same brain pathways as remembering the past.

And it turns out that remembering

the future is a better way to plan for it.

Samuel Arbesman’s The Half-Life of

Facts makes a book-length case for the hazards of assuming the future is going

to be like the present.

excel by planning further into the

future than others, our decision-making improves when we can more vividly

imagine the future, free of the distortions of the present.

because we start at the end.

Frederick Law Olmsted designed

Central Park,

Central Park when it opened to the

public in 1858

The most common form of working

backward from our goal to map out the future is known as backcasting. In

backcasting, we imagine we’ve already achieved a positive outcome, holding up a

newspaper with the headline “We Achieved Our Goal!” Then we think about how we

got there.

Imagining a successful future and

backcasting from there is a useful time-travel exercise for identifying

necessary steps for reaching our goals. Working backward helps even more when

we give ourselves the freedom to imagine an unfavorable future.

Premortems: working backward from a

negative future

We generally are biased to

overestimate the probability of good things happening.

Backcasting and premortems

complement each other.

Backcasting imagines a positive

future; a premortem imagines a negative future.

We can’t create a complete picture

without representing both the positive space and the negative space.

Backcasting reveals the positive space. Premortems reveal the negative space.

Backcasting is the cheerleader; a premortem is the heckler in the audience.

Rethinking Positive Thinking:

Inside the New Science of Motivation,

people who imagine obstacles in the

way of reaching their goals are more likely to achieve success, a process she

has called “mental contrasting.”

Oettingen recognized that we need

to have positive goals, but we are more likely to execute on those goals if we

think about the negative futures.

we didn’t lose weight;

“Okay, we failed. Why did we fail?”

Imagining both positive and

negative futures helps us build a more realistic vision of the future, allowing

us to plan and prepare for a wider variety of challenges, than backcasting

alone.

We make better decisions, and we

feel better about those decisions, once we get our past-, present-, and

future-selves to hang out together. This not only allows us to adjust how

optimistic we are, it allows us to adjust our goals accordingly and to actively

put plans in place to reduce the likelihood of bad outcomes and increase the

likelihood of good ones. We are less likely to be surprised by a bad outcome

and can better prepare contingency plans.

Dendrology and hindsight bias (or,

Give the chainsaw a rest)

One of the goals of mental time

travel is keeping events in perspective.

think about time as a tree.

The trunk is the past.

The branches are the potential

futures.

Thicker branches are the equivalent

of more probable futures, thinner branches are less probable ones.

The place where the top of the

trunk meets the branches is the

present. There are many futures,

many branches of the tree, but only one past, one trunk.

hindsight bias—the human tendency

to believe that whatever happened was bound to happen, and that everyone must

have known it.

we no longer think of it as

probabilistic—

memorializing the scenario plans

and decision trees we create through good planning process, we can be better

calibrators going forward.

Instead of living at extremes, we

can find contentment with doing our best under uncertain circumstances, and

being committed to improving from our experience.

Hillary Clinton had been favored

going into the election, and her probability of winning, based on an

accumulation of the polls, was somewhere between 60% and 70%, according to

FiveThirtyEight.com.

Nate Silver, founder of

FiveThirtyEight.com and a thoughtful analyzer of polling data.

With the constant stream of

decisions and outcomes under uncertain conditions, you get used to losing a

lot.

We can always, however, make a good bet. And even when we make a bad bet, we usually get a second chance because we can learn from the experience and make a better bet the next time.

www.howidecide.org